I finally got around to reading “To Kill a Mockingbird.” It is now a staple of the high school curriculum, but it was not in my day. I’m not sure it had been written yet. It is a terrific book that, to my surprise, centers on the ethos of a small Southern town, a place where people have known each other and each other’s families forever. In a larger city, we present one side of ourselves to the people we meet for coffee. In a small town, people see each other in the round. I was born in Turkey, Texas, in the Texas Panhandle. When I would ask my cousin what the population was, he was able to calculate it this way: Well, the McCorkles has twins, and Sally Sue ran away with a travelling salesman, so it is 994. (Today, it is half that. Such are the winds of change. When I visited it a few years ago, my dad asked, “Has it blown away yet?”)

My relatives who lived there were the best folks I have known. They were astute observers of people, events, and, above all, of character. They did not expect anybody to be perfect and they lived prudently with that fact. They knew how to make judgments without being judgmental. “He’ll work hard as long as you are looking,” was typical of this style. They were great story-tellers because small town life, when you know the people in all their lights and shadows, and take a benign view of their peculiarities and peccadillos, is full of stories.

Harper Lee’s novel is like that. It is told through the eyes of two children. When we are kids, we try to make sense of our world. As we grope at understanding, we get it half-right and half-wrong. His sister cannot remember a time when she wasn’t able to read. She is criticized by her teacher for reading “above grade level.” Her brother explains that this is a teacher newly minted by the state university. She believes in the “Dewey decimal system,” which says that, “if you want to know about cows, you don’t read about them, you milk one.”

Their father, Atticus Finch, is an attorney, respected in the community. He is perfectly embodied in Gregory Peck in the movie version. In typical small-town tolerance, he explains that nobody expects a certain family to abide by the rules. Their kids show up the first day of school and never attend after that. The school just marks them down as present. Atticus explains that, with a father who lives on home-brewed liquor and whatever game he can kill (in season or out), everybody just lets them be. In the calm wisdom of Atticus, the novel teaches moral humility. He never looks for a fight, but does not refuse one when it comes his way. In a small town, you mainly avoid and, whenever possible, defuse conflict. But,.when he is asked to defend a young black man accused of assault, he takes the case. And sticks with it, even in the face of an angry mob.

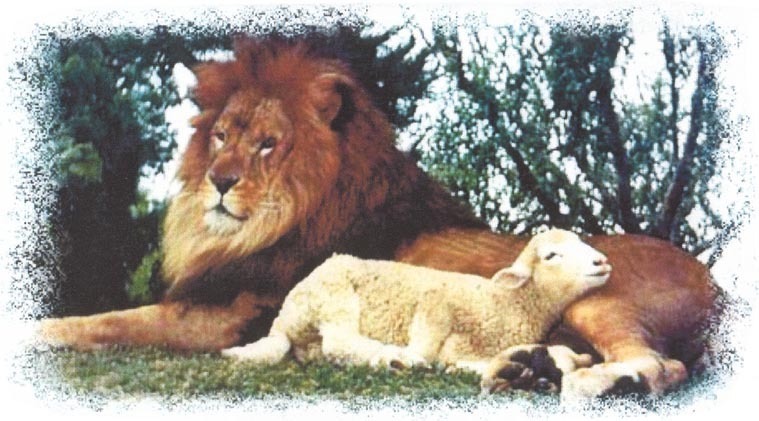

Throughout the book, there are gentle moral lessons – lessons of honesty and decency – but the only explicit teaching is that it wrong to kill a mockingbird, who is just there to sing. Perhaps we are mainly mockingbirds and should be left to sing our own song, in tune or not.