Empty suffering:

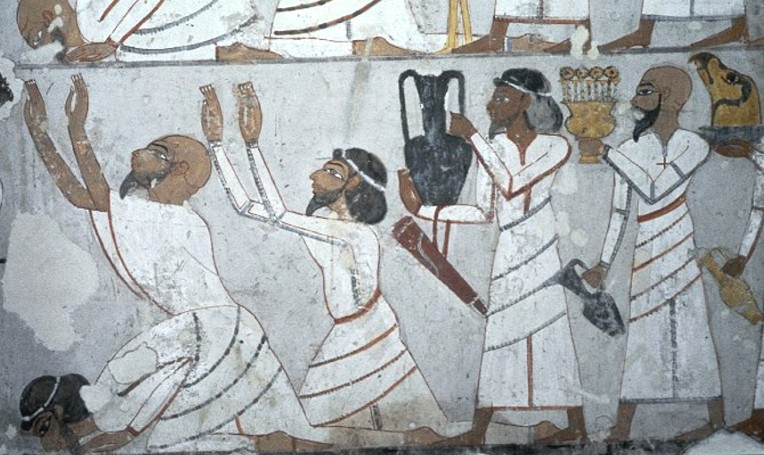

Any person who believes in God has to confront the problem of human suffering. Why does God permit it?

“Lord, does suffering have any purpose or meaning?”

Of course, suffering is what makes life serious. Imagine a world in which actions never resulted in suffering. Imagine a world without the pain of regret, without feeling bad about doing something wrong (or) shameful.

“But disease serves no moral purpose.”

Now you are fencing with Me on “the problem of pain.” Just listen. You will never learn from fencing.

Disease, disaster, aging, death are essential aspects of suffering. “We” live in a physically vulnerable world. That is the essential condition that makes life serious.

“All that’s rather abstract, Lord. What exactly does disease do for us?” I thought of Job’s boils.

Suffering is the test of your humanity. There is no greater test than pain—how one copes with it. It is easy to be nice, faithful, and such, when things are great, but very hard under adversity.

“But, Lord, that just seems perverse—or cruel.”

No, that’s not so. Think about your own times of physical suffering—in the hospital, for example—the shots, the clumsy aide, the itch, the nurse about urinating, those were full of growth.

Those examples brought back memories.

A couple of years before these prayers began, I suffered a mild heart attack and was rushed to the intensive care unit. They took blood tests, day and night. There are a limited number of places from which blood can be drawn, and the same spot cannot be used again right away. The wrists are ideal, but mine are sensitive and a needle there smarts.

One does not have much power as a patient, but safeguarding my wrists became my prime imperative.

One after another blood drawer would come, and I would plead, argue, wheedle, and insist they find some other place to puncture me. Each resisted, then managed to find a spot.

I was transferred to another hospital for the surgical procedure. I was met by a technician who said his name and stuck out his hand—while looking the other way and standing on my oxygen tube. When it was time to go into the operating room, he snatched away my blanket with so violent a jerk it would have ripped out the intravenous insertion if I had not by now been on high alert.

Once in the operating room, I was placed on a slab with my arms flat at my side.

Medical equipment loomed above, posing an impressive threat. “Don’t move!” I was told. My nose chose that moment to itch. The itch grew intense, then more intense, dreadfully intense, until nothing existed but me and that itch. Then I understood. I can’t fight it…just have to live with it, until the procedure is over. I don’t know if the itch went away or what—I forgot all about it.

The procedure went smoothly.

I watched the monitor as the surgeon snaked a catheter through an incision in my groin up to a major coronary artery where a stent had to be placed.

Opening an artery is a very serious matter. Bleeding can be life-threatening. The patient has to lie flat and immobile for twenty-four hours. Nurses at my first hospital had been angels in white, but here I was attended by Nurse Ratched’s less charming twin.

She seemed to resent patients needing her help.

Finding it difficult to manage the bedpan flat on my back, I asked for assistance. She acted as if it were a dirty-minded request and responded by threatening me, “If you can’t manage the bedpan, we will catheterize you!” Finally, I did manage, and it was time to close up the artery. Another patient had told me the closing could be dangerous as well as painful.

“Who is to perform this delicate operation?”

Nurse Ratched gave me the grim news: young Mr. Sizzorhands, the technician whose previous efforts to hurt me had been foiled, would now have another shot. I asked for someone else. “He is the only technician available.”

“I am not going to let that guy lay another hand on me.”

She made it a battle of wills. We went back and forth. Finally I said, “Let me speak to the doctor.”

She said she would see what she could do and, after a time, she returned with a young Asian-American attendant. He had magical hands. I didn’t feel a thing.

My body was recovering nicely, but the whole experience—starting with “indigestion” in the night (I didn’t know that was a heart symptom), calling the office the next morning to find out what nearby doctor was covered by my health plan, driving myself (fool that I was) to the doctor’s office, filling out forms and waiting for some time before going up and telling the receptionist, “I may be having a heart attack,” the quick examination and discovery that I was at that very moment in the throes of an incipient attack, an emergency medical team rushing to my side trying to head it off, being shoveled into an ambulance, the sirens, intensive care, the surgery, the whole ordeal—left me feeling fragile, as if I were made of spun glass. A sharp tap and I would shatter.

They (these moments) were not empty suffering; they even had to do with leading you to Me.

“How so, Lord?”

They focused your attention on your mortality, which (led) you to open your heart fully to Abigail because you realized how precious this love was. And it led to your prayer to serve God.

God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher – is the true story of a philosopher’s conversations with God. Dr. Jerry L. Martin, a lifelong agnostic. Dr. Martin served as head of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the University of Colorado philosophy department, is the founding chairman of the Theology Without Walls group at AAR, and editor of Theology Without Walls: The Transreligious Imperative. Dr. Martin’s work has prepared him to become a serious reporter of God’s narrative, experiences, evolution, and autobiography. In addition to scholarly publications, Dr. Martin has testified before Congress on educational policy. He has appeared on “World News Tonight,” and other television news programs.

________

Listen to this on God: An Autobiography, The Podcast– the dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin.

He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.