Enter My heart:

It all seemed intolerably bizarre. I thought I should talk it over with the wisest people I knew. One, a distinguished medical ethicist, responded, “First of all, this is not weird.” Nothing he could have said would have been a greater relief to me! Another, a well-known author, said, first, “That’s great—now you know there is a God,” and then added, “You have had a Kierkegaard moment,” recalling that philosopher’s question, “If you encountered Jesus on the streets of Copenhagen, would you follow him?” A prominent lay theologian said he was “touched” by my story and suggested some reading while I waited for my “big” assignment.

While there were also cautionary responses, no one seemed to think I was crazy or a fool to take the voice seriously.

Still, I was not prepared for the next experience.

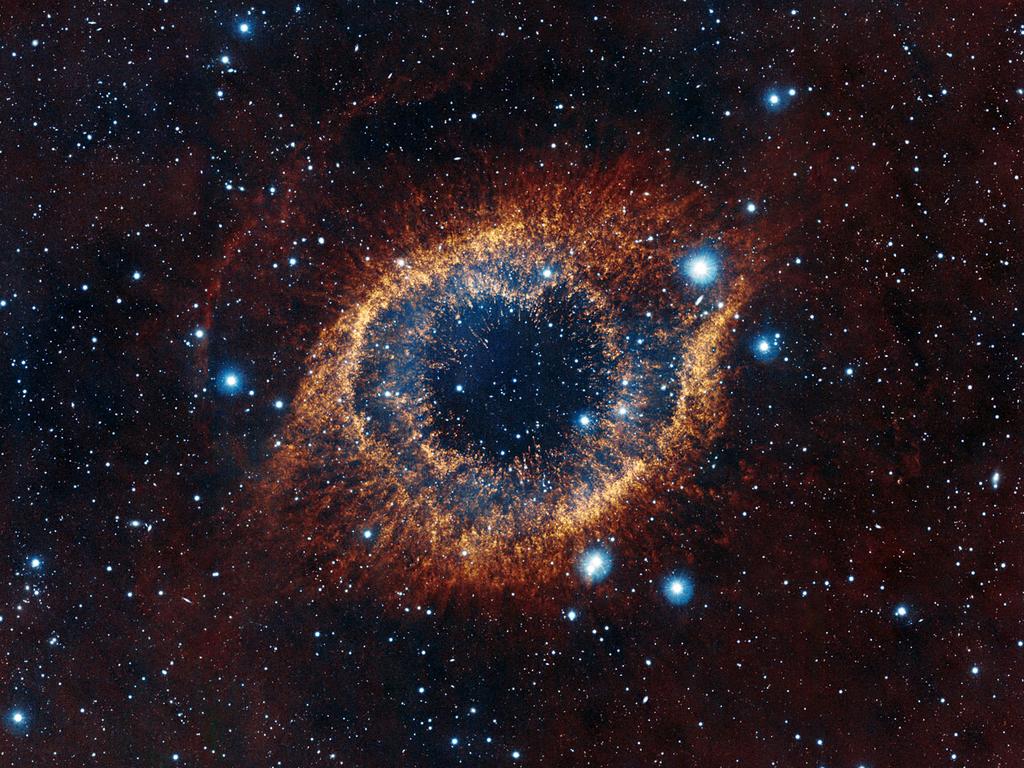

I want you to enter My heart.

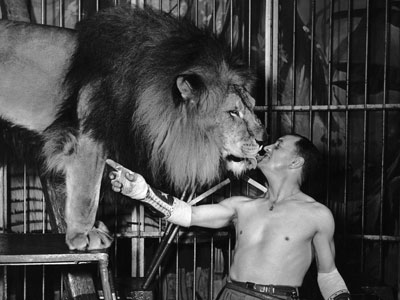

“Enter God’s heart? This is weird, Lord, and scary, like out-of-body travel.”

I will protect you.

For moral support I asked, “Lord, first give me Your love.”

Let Abigail love you. You will feel My love through her.

“Then strengthen me, be with me, for this.”

I will.

He took my hand, as it were, and led me into the “heart of God.” I had expected it to be an overpowering, perhaps terrifying experience. But it was more like the eye of a hurricane. I was at the center of something vast and powerful, but here it was quiet, calm, and peaceful. I surveyed the things I feared—the end of my career, loss of reputation, financial insecurity, and a book that went nowhere. In that calm that is God, each concern disappeared.

God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher – is the true story of a philosopher’s conversations with God. Dr. Jerry L. Martin, a lifelong agnostic. Dr. Martin served as head of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the University of Colorado philosophy department, is the founding chairman of the Theology Without Walls group at AAR, and editor of Theology Without Walls: The Transreligious Imperative. Dr. Martin’s work has prepared him to become a serious reporter of God’s narrative, experiences, evolution, and autobiography. In addition to scholarly publications, Dr. Martin has testified before Congress on educational policy. He has appeared on “World News Tonight,” and other television news programs.

________

Listen to this on God: An Autobiography, The Podcast– the dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin.

He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.