Jerry L. Martin on Discernment, Writing Prayer, and Listening for God

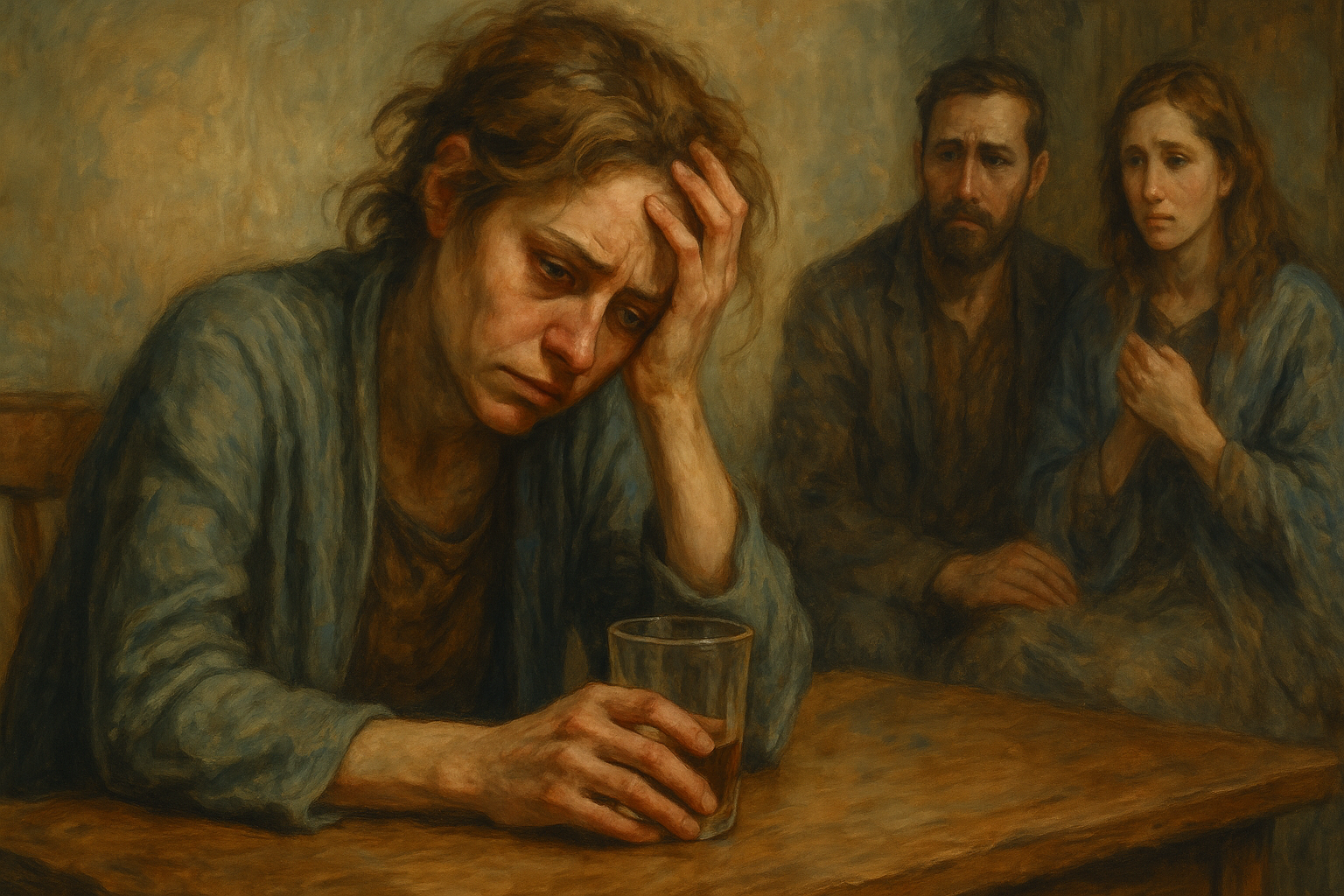

A reader of God: An Autobiography, asked me to pray and get divine guidance for a situation in which he is uncertain how to help a friend. The following is my response:

Dear A.,

I understand why, when a friend is in extremis, you worry over how to be helpful, since, in delicate situations and with unknown factors, one can easily trip over oneself. However, my assignment does not include being a medium. I did that once, putting to God a question asked by a life-long friend. I felt beforehand that God did not want me to play that role. However, I went ahead and asked. God answered but I felt I had done the wrong thing, and I have not done it again.

Let me suggest this. My best method is to sit down with a blank sheet of paper (I never do it at the computer). I put the date at the top and address my question in the following fashion: “Lord, …” (Use whatever mode of address feels most natural to you.) Even though God presumably knows these things, I state the gist of the facts and also my own feelings about the situation. If I follow up with something vague like “Lord, do you have anything to tell me about this,” I often get the response, “What is your question?” Prayer always works best if I ask a particular question.

Try this yourself. And then write down whatever comes to you. It need not be a voice, but may be more like automatic writing. Don’t edit it yourself as you go along, as if you could anticipate God’s answer. Proceed on the assumption that there is some divine element in what comes to you. If you have a follow-up question, go on in the same fashion, as long as you have genuine, honest questions.

If the answers you receive don’t make sense or seem completely wrong-headed (“That can’t be right!”), then tell God that and see how God responds. If it still seems like a muddle, then wait a day or two and pray about it again.

There is nothing guaranteed in this way of praying but, if you make it a practice, you will get better at it and establish a better connection between yourself and God. And this will be a blessing!

Warm good wishes,

Jerry