On a visit to Colorado, I told a former colleague in the philosophy department about my experiences. I was afraid he would think, “poor Jerry, he has gone daft.” But he listened with interest and respect, and recommended that I read American philosopher William James’ classic essay, “The Will to Believe.”

A British scientist had argued in an influential essay called “The Ethics of Belief” that it is always wrong to believe something without sufficient evidence. He had religion in his crosshairs. But, James responded, there are some beliefs that, if you accept them, will shape your whole life. And shape it in a different way if you do not. You cannot remain neutral; yet evidence is inconclusive either way. In these cases, it is perfectly reasonable to accept the belief even with “insufficient” evidence.

My situation seemed to be exactly what James was describing. Facing a similar choice between belief and unbelief, the seventeenth-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal, saw it as a wager. If I believe in God and am wrong, well, I’m dead anyway, so I haven’t lost much. But if I don’t believe in God, and there is one … well, you might say, there’s hell to pay.

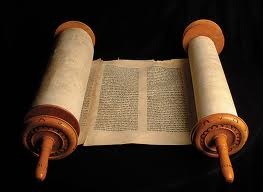

I faced my own wager. Either I follow the voice or I don’t. If I follow the voice and it is not the voice of God or anything close to that, what is the worst that can happen? Well, I would be a fool, maybe even a laughingstock, and say goodbye to an excellent career. But, if I decide not to follow the voice and it is indeed the voice of God or something close to that, then I would have really blown it. What if Moses had done that? Or George Fox, the founder of the Quakers? The Old Testament is full of people called by God, who at first demur and only reluctantly heed the call. Even Moses worries (“suppose they do not believe me”) and feels inadequate to the task (“I have never been eloquent … I am slow of speech and slow of tongue”).

I am not comparing myself to these great religious leaders, but all of us in our lives face moments when we have to decide whether to respond to a certain call—be it the call of duty or service or simply, as Joseph Campbell puts it, to “follow your bliss”—rather than continue a more conventional or comfortable course. If I had to live with one worst-case scenario or the other, I could live with being a fool, if that’s what it came to, but I could not live with having refused God’s call.

Making a decision to believe is not quite the same as accepting that belief in your bones. It is more like the first step toward believing. My philosophy still had no place for God—especially for a God who talks to me. Outside the Bible, who talks to God?

________

Listen to this on God: An Autobiography, The Podcast– the dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin.

He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.