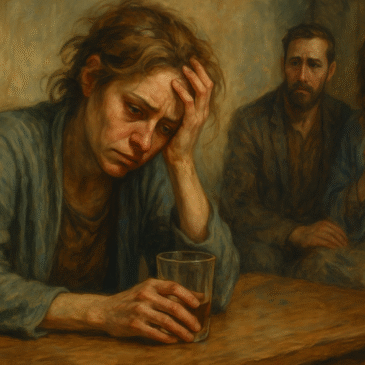

A friend contacted me about the following problem. She is related to a woman who uses her addiction aggressively to manipulate those around her. She asked what I think about this problem psychologically and theologically.

Psychologically, the woman has an addiction. Presumably, there are physical aspects to that. But she also has a psychological addiction, first to drink, more fundamentally to thinking of herself as a victim (including of those who most love her and offer help). And hence as having a right to be angry and to strike back at others (perhaps especially those who most love her and are most eager to help). She probably does not well love herself, doesn’t see herself as lovable, and hence sees those who love her as fools, especially if they let her take advantage of them, and therefore as contemptible.

Those who offer assistance and advice are her enemies, because, at the heart of her cherished victimhood is a sense of lack of agency. The one thing she can do is to hurt those who love her, and the weapon she wields is suicide. She can end it all and that will teach them! Let them live with the hurt and guilt (which, unfortunately, they are almost certain to feel) for the rest of their lives. How can a person decide to end her life? The character that defines a person has long since been emptied out by drink and fantasy victimhood and behaviors, ugly even in her own eyes, that break healthy ties to others and undermine self-respect. So the completely self-indulgent self ends up with no self worth perpetuating. There is nothing left to hold onto. What meagre shred remans offers less satisfaction than dramatically striking back through suicide. Psychological models tend to run aground here. Most of them are deterministic. Her troubles, they say, are the fault of a bad childhood, or of “society” (which, oddly enough, is spoken of as if it had agency, i.e., makes us do or think this or that, of which we are then victims).

So what do we say about all this theologically? For Christians (like my friend), the vital theological concepts are sin and grace. For grace to be operative, a person might well need to understand her own sin. And sin implies agency, free will, so the woman in question can’t go there, and those aspects of our culture that deny agency, including many in the helping professions, can’t go there. So her sin, as sin, remains unattended and unrecognized. There are many conduits of grace, but among them are the people who love us and those who, for humane reasons, want to be helpful. The nature of sin is that it does not want to be “helped.” The alcoholic does not want “help,” does not want even to recognize his or her condition, his or her “sin.” We can close ourselves off to grace: “inwardness with the door closed,” as someone called it. God sometimes breaks through extraordinary barriers – grace can reach the drunk with his face in the gutter — but the agile sinner can stave it off until it is too late.